|

Robert Graham, the laird of Gartmore enslaved and traded in human beings. This was documented by R B C Graham in his account of his great-great grandfather’s life, Doughty Deeds […](1925); by Dr Michael Morris here; by Dr Stephen Mullen here; and by me in this 2016 blog post, among others. A map of Gartmore House and surroundings made during the time George Oglvie worked there. From 'A Book of Plans of the Estate of Gartmore, Belonging to Robert Graham Esqr. Surveyed and Planed by Charles Ross', 1781. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland. Robert Graham and his wife Anne Taylor were personal enslavers; not just on their two plantations in Jamaica, but in Scotland too. They took at least two enslaved people with them when they returned to Scotland around 1770: a man they called Martin, who was sent back to Jamaica in 1773 and a man they called Tom, who remained with the Graham family and is said to have been buried at the family lair at Gartmore House. Nothing more is known about the men, as far as I know. It is tantalising and frustrating in equal measure to think that two enslaved human beings lived their lives right here, on my doorstep, but that I’m unlikely to ever know anything about their existence. There is one person in the Graham family’s service, however, about whom we can know something: their butler, George Oglvie. George Oglvie worked as a butler for the Grahams from at least 1778 until maybe 1789. When exactly he came to Gartmore, and from where, I haven’t yet been able to discover. If he arrived from Jamaica along with the Grahams it has not been documented, to my knowledge. I know that George was most likely Black and may have worn livery; that Robert Graham bought him breeches, shoes, a horse, a silver watch and a double-barrelled gun, and maybe a Bible; and that he had access to money (NLS, Acc.11335/186). My reason for thinking he was Black is down to one single, but carefully worded, entry in the minutes of the Kirk Session of Port of Menteith Parish for January 1783. It appears that George was the father of a child born out of wedlock to a former fellow servant named Margaret McEntyre. The entry for New Year’s Day 1783 reads: Margaret McEntyre, late Servitrix in the House of Gartmore was convicted of being with Child in Fornication and gave up Gartmore’s Æthiopian for its Father; she being then suitably admonished, was desired to attend when called. (NRS CH2/1300/3) The word ‘Æthiopian’ was one of many terms frequently used by white people to refer to Black Africans, a form of stereotyping and othering. The Kirk Session clerk evidently felt it pertinent to point out that George Oglvie was a Black man and that he belonged to Gartmore, thereby singling him out as different in a way that didn’t happen with other parishioners. I have not come across any other instances in the Kirk Session records, so far, of descriptors of this kind being applied to anyone. In July of the same year George Oglvie appeared before the Kirk Elders to acknowledge the child as his own and to pay his fine. The entry reads: George Oglvie Gartmore’s Æthiopian acknowledged himself to be the Father of Margaret McEntyre’s Child whom she gave up for its Father as above exprest (NRS CH2/1300/3) Whether George Oglvie was, or had been, enslaved by Robert and Anne Graham is unclear. George’s presence is documented from around 1778 (NLS, Acc.11335/186-7), the same year that a famous ruling by the Court of Session effectively made slavery in Scotland illegal. It would have been difficult, and unlawful, after 1778 for the Grahams to keep George enslaved or in perpetual servitude. The fact he had a surname, unlike Martin and Tom, suggest that George’s individual status in society was different than theirs. So, while he may not have been enslaved, and while he did receive a salary as well as clothing and medical care, this does not mean that his relationship with the Grahams was not coercive or exploitative or that he could simply walk away if he wanted to. I don’t know what happened to Margaret McEntyre or to George or their child, except it appears she was no longer a servant at Gartmore House by the time her pregnancy was recorded at the Kirk. Did the Grahams dismiss her when they discovered she was pregnant with George’s child? It reminds me of poor Annie Thomson who was dismissed by her employer John Wedderburn (another Perthshire laird and enslaver) when she was pregnant with Joseph Knight’s child. Curiously, a few weeks later, in mid-August 1783, a little boy was baptised in Port Kirk. His entry in the Old Parish Registers reads: George natural son to George Oglvie & Christian Wright both in Gartmores Service (NRS OPR Births 388/ Port Of Menteith, p.273) Did George Oglvie father two children with different women at the same time? Or did the Kirk clerk mistakenly write down Christian Wright when he meant to write Margaret McEntyre? Or, less likely perhaps, could there have been two George Oglvies in Port Parish at the same time, and both employed by Robert Graham? I hope further searches at the National Records of Scotland and the National Library of Scotland will produce more clues.

If you happen to know anything about George Oglvie please leave a comment in the box below, thank you :-) Sources: Cunninghame Graham, R.B. 1925, Doughty deeds: an account of the life of Robert Graham of Gartmore, poet & politician, 1735-1797, W. Heinemann, Ltd, London. https://stirling.spydus.co.uk/cgi-bin/spydus.exe/ENQ/WPAC/BIBENQ?SETLVL=&BRN=3494015 National Library of Scotland: Correspondence, notes, literary papers and other papers of the Cunninghame Graham family, mostly of Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham; and financial and administrative papers relating to Gartmore and Ardoch. Acc.11335/1-227 https://digital.nls.uk/catalogues/guide-to-manuscript-collections/inventories/acc11335.pdf National Records of Scotland: Male servant tax rolls 1777-1798 for Perthshire and Dumbartonshire https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/digital-volumes/historical-tax-rolls/male-servant-tax-rolls-1777-1798 National Records of Scotland: Port of Menteith kirk session, Minutes (1773-1789), Accounts (1773-1800), CH2/1300/3 National Records of Scotland: 1783 OGLVIE, GEORGE (Old Parish Registers Births 388/ Port Of Menteith) Page 273 of 515 Slavery, freedom or perpetual servitude? - the Joseph Knight case https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/research/learning/slavery/slavery-freedom-or-perpetual-servitude-the-joseph-knight-case

0 Comments

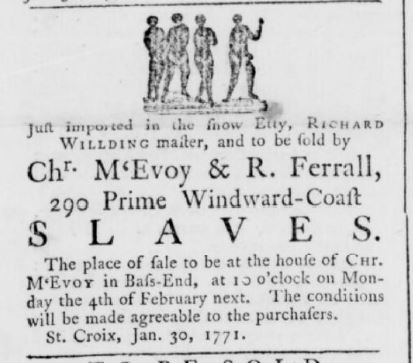

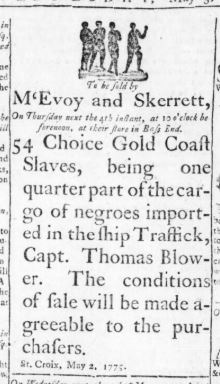

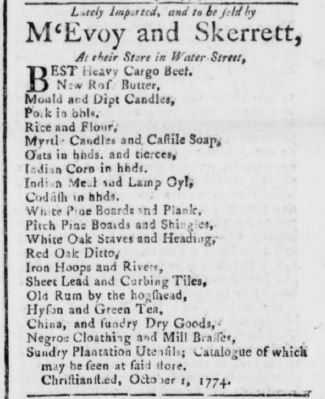

The MacEvoy family of West India planter-merchants caught my eye recently because of their close ties to Copenhagen and the island of St Croix in the former Danish West Indies, and because of their often repeated but unsubstantiated origins in Scotland. That the family originated in Scotland was stated by C.F. Bricka in his entry on Christopher MacEvoy Jr (c. 1760-1838) published in the 1897 edition of the Dansk Biografisk Lexikon (the Danish dictionary of national biography). Author and historian Kay Larsen restated it in his notes on MacEvoy compiled before 1928. One source refers to Christopher MacEvoy Sr (c.1719-1792) as ‘a newcomer from Scotland’, ‘a Catholic refuge, complete with Coat-of-Arms’, who arrived ‘on St. Croix in 1751’. Another source even pinpoints MacEvoy’s origins in Fife, Scotland. None of these publications is referenced, however, and the sources regarding MacEvoy’s Scottish heritage which the publications may have relied on, remain unknown. Notwithstanding the insubstantial research on MacEvoy published during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and the few mentions the family have had since, the primary archival sources of the former Danish West Indies held in the Danish national archives are littered with the name MacEvoy. It is clear that the family owned significant property in both St Croix and Denmark and that they were well-connected members of the business community in both places. More recently, research by Dr Orla Power has placed the MacEvoys among the Irish diaspora in the Danish West Indies alongside major players like the Farrell, Tuite and Skerrett families. In fact, research by Jørgen Bach Christensen has argued that the MacEvoys and the Heyligers were the top two property owners in St Croix, each owning more acres of land than any of the other families. Dr Power states that many of these Irish-Caribbean families had come to St Croix from the British Leeward Islands – she writes: “By 1747, a group of Irish merchants and planters with family connections in Ireland, Montserrat and London, had begun to purchase land at Saint Croix”. This date chimes with the reported arrival in 1751 of Christopher MacEvoy Sr in St Croix. Burkes’ ‘A genealogical and heraldic history…’ suggests a link between the MacEvoys and a MacEvoy family in Co Longford, but some of the detail is possibly confused. This is odd as Sir Bernard Burke himself married into the MacEvoy family and should have been well versed in the family history of his wife Barbara Frances MacEvoy. I am thankful to James Kennedy in Kinlochard for pointing me in the direction of Irish sources that may help to clarify this potential Co. Longford connection. So, it seems I can forget about the alleged Scottish link and focus on the MacEvoys as key components of the island’s Irish diasporic planter-merchant community. Although existing histories of the MacEvoys puts Christopher MacEvoy Sr in St Croix by 1751 his name appears more frequently in the digitised documentary sources from around 1756 onwards. By the beginning of 1773 he owned, or co-owned, at least five plantations in the island including: Estate Granard in Company’s Quarter, managed by Christopher Nugent. On this estate MacEvoy kept 162 enslaved people – this number was made up of 109 ‘Able negroes’, 8 ‘Manquerons’ (infirm, elderly or unable to work), 7 ‘Half-growns’ (between the ages of 12 and 16) and 38 children under the age of 12. Estate Longford in Company’s Quarter, owned jointly with his business partner Selby, with 175 enslaved people, including 36 children. Estate Belview in Company’s Quarter, which was managed by Peter Neale and where MacEvoy lived with his wife Maria and three children. Here he kept 104 enslaved people. Estate Spring Garden in Northside Quarter where he kept 72 enslaved people. Estate Cane Garden in Queen’s Quarter, managed by William Usher, where he kept 53 enslaved people. In that year alone, MacEvoy was responsible for an enslaved workforce of at least 577, including the 11 people he kept in his town house in Queen’s Cross Street, Christiansted – one of six properties owned by him in St Croix’s main town at that time. The St Croix lists of enslaved labourers and other inventories provide the facts and figures of how the island’s plantations were ‘staffed’. We know the names of the plantation owners, the managers and the overseers. We know what the enslaved workers were called – the men were given names like Limerick, Cudjoe, Johannes, Cato, Christmas and Mulatto John, while the women were given names like Phillis, Moll, Mimba, Frankey, Prudence and, in one case, Monasyllable. We sometimes know what their owner had paid for them and what they were deemed to be worth when taxes were due. The brutality, the exploitation, the forced separation of children from their mothers, the rape, the systemic violence and the methodical punishments, that we know was part of chattel slavery is not recorded in these lists. They simply give us a conservative estimate of the number of enslaved Africans, in a given year, for whom this was life. By early 1774 MacEvoy had added estate Orange Grove in Company’s Quarter to his portfolio. Here he kept 112 enslaved people, while at Cane Garden he increased numbers from 53 to 87, suggesting perhaps he was in the process of developing the plantation or intensifying production. In addition to his plantations MacEvoy operated as a merchant in Christiansted in partnerships with Roger Ferrall and Marcus Skerrett. Newspaper adverts of the time provide some insight into the nature of these businesses: they involved both slave trading and import of essential provisions for the island’s planters. By at least 1770, if not much earlier, MacEvoy was trading in enslaved Africans - a newspaper advert for two runaways refer to one as having been bought from MacEvoy & Ferrall. An advert in January 1771 by MacEvoy & Ferrall advertised the upcoming sale of 290 people from the Windward Coast [West Africa]. They had been shipped on board the snow ‘Etty’ by Richard Willding (this could possibly be the well-known Liverpool based enslaver of the same name) and were to be sold at MacEvoy’s house in Bassend (Christiansted) a few days later. The ship, however, was diverted to Jamaica and we may assume that its cargo was sold there. In May 1775 MacEvoy & Skerrett advertised the sale of 54 ‘Choice Gold Coast Slaves’, part of a cargo of around 216 people imported on board the ship ‘Traffick’. With Marcus Skerrett MacEvoy also traded in foods and provisions for the St Croix planters from their store in Water Street, Christiansted, as well as sending ships return to Copenhagen, presumably laden with sugar or other colonial goods. In 1776, aged approximately 57, Christopher MacEvoy placed an advert in the paper announcing his intention to relocate to Copenhagen in April of that year. He wound up his business partnership with Marcus Skerrett, applied for Danish naturalisation and left his plantations in St Croix to be managed by attornies and family members. In Copenhagen he entered the former co-partnership of Chippendale, Selby and Co which, from 1777, traded as MacEvoy, Selby, Dungan and Thompson. As a co-partner in this company MacEvoy continued to pursue his colonial interests as an absentee plantation owner and West India merchant and commissioned the building of at least one merchant vessel destined for the West India trade. The company also had interests in at least one sugar house as well as acting as Copenhagen agents to several other St Croix planters. In the same year MacEvoy purchased Count Reventlow’s town house in Copenhagen, complete with hereditary Reventlow furniture and silverware, as well as the country estate of Christiansholm. MacEvoy’s trajectory at this point in time thus fits neatly into to a wider pattern of English-speaking, planter-merchants, many of whom were Catholic, and who all went down similar paths (i.e. St Croix planter-merchants who move to Copenhagen, become naturalised Danish subjects or marry into Danish merchant families, buy properties in the City and estates in the country, are extremely well-connected in Royal, political and commercial circles and who continue to own plantations in St Croix while trading in West Indian produce from Copenhagen, particularly sugar). These include: MacEvoy’s business partner Charles Selby (1755-1823), who arrived in Cophagen in 1773 and entered the merchant house of William Chippendale (trading in Copenhagen from c. 1760). MacEvoy’s business partner John Dungan, a Copenhagen-based sugar merchant from Granard, Co Longford. Theobald Bourke (1724-83) (naturalised 1779) and Edmund Bourke (1761-1821), Irish planter-merchants in St Croix, who arrived in Copenhagen c. 1782. Philip Ryan (1766-1807), St Croix-born Irish ship’s captain and planter-merchant who arrived in Copenhagen c. 1780. Around the time of his relocation to Copenhagen MacEvoy had acquired estate Barren Spot in King’s Quarter where he kept 89 enslaved people, plus two named Scipio and Simon who had run away, increasing his holdings, at that point in time, to an estimated 814 enslaved people. Barren Spot had belonged to MacEvoy’s wife’s mother, Elizabeth Markoe (nee Cunninghame), who left it in her will to her children. It appears to have been the subject of a legal dispute between MacEvoy and the Markoe heirs the date of which ties in with the time MacEvoy became the proprietor of the estate. The probate documents are held in the Rigsarkivet and record what appears to be a long and drawn out settlement of Elizabeth’s estate, which began one week after her death. Parish records indicate that MacEvoy’s wife (Elizabeth’s daughter) Maria Markoe had died in Copenhagen in December 1776, and it is possible that her share in Barren Spot, which her mother had assigned to her in her will, had passed to Maria’s husband. Whatever the case, details of MacEvoy’s acquisition of Barren Spot is likely to be contained Elizabeth’s probate. Having remarried in 1778 Christopher MacEvoy seems to have spent his time between Copenhagen, St Croix and London until around 1791 when his health began to fail him. Christiansholm was sold in 1783 to Count H.E. Schimmelmann, Denmark’s Finance Secretary, director of the country’s ‘Guinea trade’ (= trade in enslaved people) and one of the largest plantation owners in St Croix. In St Croix, MacEvoy’s sons Michael and Christopher Jr began to sort out their fathers business affairs and advertised long-term leases on his town houses in Christiansted. Christopher MacEvoy died in London in the summer of 1792 and was buried at St Pancras Old Churchyard in Camden. The epitaph on his headstone was recorded by F.T. Cansick in 1869, it reads: 'Here lie the remains of Christopher McEvoy, Esq. Late of the Island of St Croix, who Departed this Life the Eleventh day of July, 1792, In the 73 year of His age, Firmly hoping through the Mercy of God and the Merits of Christ to obtain eternal Peace. So be it. Amen. He was a tender, kind Husband and affectionate Father, An indulgent Master, and strictly honourable in his extensive Dealings. He died sincerely regretted by his Friends and universally lamented. R.I.P.' Sources:

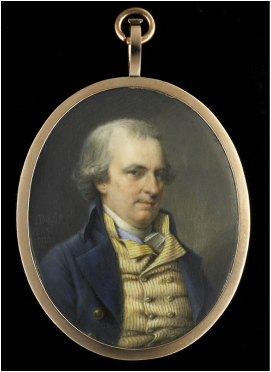

C.F. Bricka: Dansk Biografisk Lexikon, Vol. XI, 1897 Burke, Sir B. 1879. A genealogical and heraldic history of the landed gentry of Great Britain & Ireland, Vol. 2. F. T. Cansick 1869: A Collection of Curious and Interesting Epitaphs: Copied from the Monuments of Distinguished and Noted Characters in the Ancient Church and Burial Grounds of Saint Pancras, Middlesex, Volume 1, p. 68 Msgr. M. Kosak: 175th Anniversary Commemorative History of St. Anne´s Church, Estate Barronspot, 1975 – follow up to K. Larsen: Dansk-vestindiske og -guineiske Personalia og Data. Ny kgl. Samling 3240, 4° Orla Power 2007: Beyond Kinship: A Study of the Eighteenth-century Irish Community at Saint Croix, Danish West Indies. Irish Migration Studies in Latin America, Vol. 5, n°3 (November 2007) Orla Power 2011: Irish planters, Atlantic merchants: the development of St. Croix, Danish West Indies, 1750-1766 Rigsarkivet: Arkivalier Online - https://www.sa.dk/brug-arkivet/arkivalieronline http://sortefortid.dk/briterne http://www.stcroixlandmarks.com – contains excerpts from "Preserving the Legacy" by Priscilla G. Watkins on behalf of St. Croix Landmarks Society (1998) Generations of Grahams of Gartmore have been laid to rest in the small burial enclosure a short distance from Gartmore House where they lived. Nowadays this magical little lair is enveloped in vegetation – snowdrops and daffodils at this time of year – and it feels like a long time since anyone came here to mourn the dead. Inside the enclosure seven mural tablets are set into the walls, inscribed with the names of the many generations of people thought to be buried there. The central, and most elaborate tablet, which spans the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, immortalises the names of some key people in the history of the Graham family. More importantly perhaps, it lists the key individuals through whom the Graham family traced its succession to property: Sir William Graham of Gartmore who died in 1680 (and who may thus have been the first Graham of Gartmore to be buried on this spot); Isobella Bontine through whom the Grahams inherited the estate of Ardoch in Dunbartonshire, and William Cunninghame, 12th Earl of Glencairn, through whom they succeeded to the estate of Finlaystone in Renfrewshire (now Inverclyde). In this respect, the tablet is far more than just a memorial to dead ancestors; it is a material expression of the family’s hereditary claim to the three estates it owned when it was at its wealthiest. Their rights to property set in stone, quite literally. At the centre of this extraordinary accruing of land, wealth and influence sits Robert Graham of Gartmore (1735-1797), whose name is inscribed on the tablet among those of his parents, his grandparents, his son and many others. By the time he died Robert Graham had increased his family’s possessions far beyond that which any ancestor had done before him. His lands extended from Finlaystone in Renfrewshire across the Clyde to Ardoch near Cardross, to Gallangad on the Dumbarton Muir, to Gartmore and Kippen, in addition to his lands at Lochwood in Lanarkshire, and of course the property that initially set him on the road to serious wealth – his two Jamaican sugar plantations, Roaring River and Lucky Hill. Having inherited multiple estates Robert was confident that he would have sufficient ‘to enable me to support that rank and fashion to which I am entitled’. For Robert Graham his ownership of property, his personal wealth and his lifestyle were clearly a matter of entitlement. He carried out costly agricultural improvements, enlarged and embellished his country mansions at Ardoch and Gartmore and laid out the planned estate village of Gartmore. He even had a ‘Pinery’ where he experimented with growing grapes and pineapples…. Yet, for much of his adult life his attention was firmly fixed on a place far far away from his ancestral home – that place was Jamaica. Like many younger sons of the Scottish gentry, who had no immediate prospects of inheriting the family estate, Robert Graham had looked to the British colonies for career opportunities. Aged 17 he left Scotland for Jamaica where a relative of his father’s, Mr Bontein, at that time held the lucrative position of clerk of the Court in Kingston. Within a year Robert had secured the position of Receiver-General of Taxes in Jamaica. His marriage to Anne Taylor, the daughter of a Kingston merchant, and sister to Simon Taylor, Jamaica’s richest and most influential planter-merchant, further guaranteed Robert’s position among the elite of Jamaican colonial society. Generations later, his Great Great Grandson and biographer, Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham, speculated that Anne may have been a ‘Creole’ (a term often applied to a white person born in the colonies) as she is likely to have been born in Jamaica. Robert Graham and his brother-in-law Simon became business partners and over the years the two became the closest of confidantes, looking after each other’s financial interests as well as those of each other’s children and heirs. The expression ‘thick as thieves’ spring to mind….. Simon Taylor remained a bachelor all his life, but like many plantation-owners, he famously fathered a number of mixed-race children with enslaved women - ‘some almost on every one of his estates’. It was not unusual. And Robert Graham, who would go on to marry Simon’s sister, was no different. In 1760 he wrote ‘[…] I was not remarkable for that cold Virtue, Chastity, but indiscriminately found my sentiments agreeable to my desires and gave rather too great a latitude to a dissipated train of whoring, the consequence of which I now dayly see before me in a motely variegated race of different complexions’. What happened to Robert Graham’s offspring ‘of different complexions’ and their mothers I do not know. Perhaps a closer examination of his will might tell us whether he intended to provide for them in some way, like Simon did for some of his ‘West Indian families’. Robert did make arrangements for his illegitimate (white) son to be sent to Britain for education, as was common for many white colonial settlers, but little is known about him. The Roaring River estate was a slave plantation that produced sugar, rum and molasses. The produce was shipped to Greenock to be sold and the ships would return to Jamaica loaded with fresh supplies and goods for the estate. It is not known how many slaves Robert Graham owned but it is clear that he was involved with the trading of slaves within the colonies and regularly purchased new slaves to replace ones that had been worked to death at Roaring River. Simon Taylor’s letters show that he was painfully aware of the fact that the only reason his estates were making a profit was ‘because he put negroes on them […]’ and he continually worried about the future of the West Indies in the event of the abolition of slavery. However, for now, emancipation was a long way away, and for Simon and Robert keeping and trading enslaved Africans was business as usual. The slaves that lived on Robert Graham’s estate were his private property and individual slaves were occasionally sold on to new masters. In 1760 Graham sold a slave woman to a man on the Musquito Coast in Central America. Graham wrote: ‘At the Recomendation of my friend Mr. McLean, I use the freedom of consigning to you a Negroe Woman named Mary who washes extremely well and has severall other Qualifications which the Purchaser will be soon able to discover, but is endowed with such a surprizing facility of speech that I found it impossible to put up with it any longer […] You will please dispose of her to the best advantage and remit me the proceeds […]’ Around 1770-1, when Graham left Jamaica to return to Scotland, he sold a slave called Jack whom he shipped to a merchant in South Carolina, America. Graham stated that Jack was ‘a very valuable fellow’, well qualified to wait at table and ‘worth One hundred Pistols’. However, he did not part with all his slaves when he returned to Scotland. He brought at least two with him, one named Martin and one named Tom. Martin was sent back to Jamaica in 1773, as he was ‘too lively and sprightly to accommodate his disposition to the sedate Gravity of this Climate – dispose of him to the best advantage. I was offered £100 for him before I left Jamaica, and I think he is now worth a good deal more’, Graham wrote. Tom, however, remained with the Graham family. Before leaving Jamaica Tom was valued at £100, a price which Robert Graham thought was exaggerated, and instead chose to bring him to Scotland. Tradition has it that Tom was buried in the burial enclosure at Gartmore House. Unsurprisingly, there is no mural tablet in the burial lair with Tom’s name on it. Nevertheless, we may imagine that Graham felt some appreciation for Tom, and if he is indeed buried in the family burial enclosure, that this was a sort of final act of kindness extended to him. Or perhaps a final act of domination.

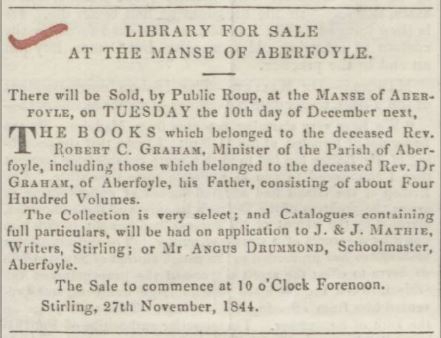

I am grateful to Peter Sunderland and staff at Gartmore House for permission to visit and photograph the Cunninghame Graham burial enclosure. Sources: Cunninghame Graham R.B. 1925. Doughty Deeds : an account of the life of Robert Graham of Gartmore, poet & politician, 1735-1797 Brown, Vincent 2008. The reaper's garden: death and power in the world of Atlantic slavery. Daniel Livesay: Extended Families: Mixed-Race Children and Scottish Experience, 1770-1820 National Library of Scotland: Inventory, Acc. 11335 , Cunninghame Graham The Taylor and Vanneck-Arcedekne Papers from Cambridge University Library and the Institue of Commonwealth Studies, University of London  Baron Constantin von Ettingshausen © Copyright Bildarchiv der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Wien. Baron Constantin von Ettingshausen © Copyright Bildarchiv der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Wien. In the summer of 1881 a pretty, young Austrian Baroness by the name of Johanna ('Hanna') von Ettingshausen married Norman Macleod of Macleod. 42 years her senior Hanna’s new husband was the Chief of the clan Macleod and recently widowed. Many years earlier, in 1849, he had been forced to give up parts of his hereditary lands in the Isle of Skye due to astronomical debts (some of which he probably inherited from his father and grandfather). The estate was taken over and run by the trustees of the family’s creditors. Macleod left his ancestral home at Dunvegan Castle and relocated to London with his first wife, Luisa, and their children. In London the Macleod family lived at first in Montagu Place in Marylebone and Macleod had to get a job to support his family. For a few years he worked as under-secretary in the Prison Department of the Home Office, before moving to the Department of Science and Art where he worked as Assistant Secretary. This Department had been transferred from the Board of Trade to the Education Department and was responsible for the administration, among many other things, of the South Kensington and Bethnal Green Museums. As such, Norman Macleod found himself working in South Kensington Museum. A decade later Macleod’s financial situation had improved and things were looking up. The family gave up Montagu Place and moved to the considerably swankier Cadogan Place in London’s Belgravia district. By 1863 Macleod was once again able to take possession of Dunvegan Castle and the family started spending several weeks there every summer. Some of Luisa and Norman’s children, who had been born in England and never set foot in Skye, were able to spend holidays there and formed life-long attachments to the place. Norman’s boss too – Henry Cole – appears to have visited Dunvegan. The British Museum have in its collection two etchings of Dunvegan Castle made by Henry Cole, signed "Dunvegan Castle / Skye. Sep / 1863 / H Cole" and dedicated to Mrs Macleod. In South Kensington Museum Norman Macleod corresponded with Colonel Lane Fox (aka Pitt-Rivers) in relation to proposed loans of objects from Lane Fox’s collection to the Museum’s branch in Bethnal Green. He also wrote to John Lubbock, J. Fergusson, Prof Huxley, E.J. Poynter, P. Cunliffe Owen, Colonel Donnelly and George Rolleston in relation to Pitt-Rivers’ proposed development of his Ethnological collections at South Kensington Museum. At this time, Baron Constantin von Ettingshausen, Professor of Botany at the University of Graz in Austria and an internationally recognised geologist and palaeo-botanist, made several trips to London where he stayed for extended periods of time. In 1876 he was summoned to London to reorganise a fossil plant collection at the Natural History Museum. In the same year he lent or donated several specimens to the Special Loan Collection of Scientific Apparatus, the organisation of which Macleod was involved with. I think it is highly likely that Norman Macleod came into contact with Baron von Ettingshausen around this time, and importantly, with the Baron’s daughter, the lovely Baroness Johanna. Then, on 27th October 1880, Macleod’s wife Luisa died, aged 62. With all the Macleod children having flown the nest, Norman moved in with his son Reginald and his family in Belgravia, a short distance from Norman and Luisa’s home. Norman continued to work in the Department of Science and Art, but things were about to change. The following summer Norman, aged 69, married Baroness Johanna von Ettingshausen in Graz, Austria. He retired from his position in South Kensington, able to enjoy retired life without financial woes, with a new, young wife and an ancestral castle to spend the holidays in. Not bad at all. While in the Isle of Skye Hanna developed an interest in the island’s archaeology. Over the years she would carry out two excavations, one at Dun Beag, the other at Dun Fiadhairt. Her first piece of work was the excavation of the Broch of Dun Fiadhairt (Dun an Iardhard) which may have taken place in 1892. Whether Hanna had any previous experience with archaeological fieldwork we do not know, but Fred T Macleod, who years later wrote up the excavation on her behalf, states that she carried out and personally supervised the work. It is evident that several workmen were involved, as the ‘over one hundred full working days’ spent on the project involved the ‘conveyance of men and necessary implements a distance of two miles across Loch Dunvegan’. Four men are mentioned by name: Donald Ferguson, Hanna’s [farm] manager; Donald’s two nephews Angus and Neil Ferguson; and Macleod of Macleod’s factor, John Mackenzie FSA Scot, who surveyed the broch and prepared plans and sketches. Donald Ferguson may be the very farm manager, who upon his retirement in 1931, Hanna presented with a Norse gold finger ring, said to be from Skye, and now in the collection of Glasgow Museums (A.1979.19). On 5th February 1895 Norman Macleod died in Paris. His body was taken to Skye and buried at Duirinish Church. Now a widow, Hanna, aged 41, was entitled to Dunvegan Castle’s dower house – Uiginish Lodge, where she would spend the summer seasons. In November 1897 she married Count Vincenz Baillet de Latour (1848-1913). At the time he was Austria’s Education Minister, and himself of European noble origins. Hanna’s new married name - Countess Baillet de Latour – is the name by which she is known to archaeologists in Scotland. Between 1914 and 1920 Hanna excavated Dun Beag broch, near Struan in Skye. The excavation was written up by J G Callander, Director of the National Museum, who records that about 200 tonnes of stones and earth were removed from the broch and that all the soils were sifted through the fingers – a technique Hanna had also employed at Dun Fiadhairt. By the time she completed her excavations, in 1920, she was 66 years old. Whether Hanna continued to explore the archaeology of the Isle of Skye, we do not know, but I imagine that she continued to spend her summers in Skye, and the winters on the continent. Perhaps in Paris where she may have lived with Norman Macleod before his death; perhaps in Graz where she had grown up, or perhaps in Vienna where she was born. In 1942 the Countess Baillet de Latour died in Arthington Nursing Home in Torquay, 88 years of age. Sources: Macleod, R. C. 1906. The Macleods: a short sketch of their clan, history, folk-lore, tales, and biographical notices of some eminent clansmen Devine, T. 1996. Clanship to Crofters War. Osbaldeston-Mitford, B. 1941. Roderick Charles Macleod of Macleod, A Short Memoir. British Newspaper Archive Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland http://www.prm.ox.ac.uk http://www.ancestryinstitution.com In Buchanan's 1902 illustrated tourist guide Aberfoyle was described like this: '...in the season, quite a gay place, with a convenient railway station, well equipped shops, comfortable villa's, ornamental cottages, exhibiting tasteful freaks of architecture, and in addition to the Parish Church an Episcopalian.'  Exactly which of Aberfoyle's buildings were thought of as 'tasteful freaks' I am not quite sure. The 'well equipped shops' most likely included Wm. Lockhart & Sons, purveyors of 'fancy biscuits of superior quality', and owners of a tea room located opposite Aberfoyle railway station, no doubt taking advantage of a considerable footfall of visitors arriving to and leaving Aberfoyle by train. In addition to Lockhart's the village's businesses also included three hotels, two of which were Temperance Hotels, two drapers, two bootmakers, two joiners and cartwrights, a dairy, two grocers one of whom also sold wine and spirits, a blacksmith, a plumber, a coal merchant, a butcher, and last but not least, a 'fancy stationer and fishing tackle dealer'. Not bad for a smallish village. But that is not all - in 1916 Surgeon Dentist, R. Stirling set up shop in the Masonic Hall at the Bailie Nicol Jarvie Hotel every second Thursday where he would offer 'Painless Dentistry' at moderate charges to his patients. His adverts stated reassuringly that 'Painless extractions by modern methods' was his speciality, saving patients from 'suffering that dreadful toothache and enduring sleepless nights because they dread the ordeal of having the teeth out'. Oh R.Stirling, where are you now?? On 13th October 1844 the Reverend Robert Cunningham Graham, minister of Aberfoyle, died at the Manse after a few days' illness. By the end of October the contents of his house were put up for sale by a public auction to be held at the Manse on 11th November 1844. The advert gives us a unique glimpse of what the minister's house contained and what his household might have been like. His belongings included dining room furniture, drawing room furniture and bedroom furniture; a set of mahogany tables, mahogany chairs, drawing room sofas and chairs; carpets, grates, fenders and fire irons; an eight-day clock, mahogany chests of drawers, dressing glasses (small free-standing mirrors); posted and tent bedsteads, curtains, feather beds and mattresses and bed and table linen. A painting of Aberfoyle by Fleming (I think this is probably the Scottish landscape painter John Fleming 1792-1845) in a gilt frame and several engravings in gilt and rosewood frames were also sold, as were the kitchen furniture and dairy utensils. For sale were also farming equipment, livestock and other farm stock suggesting that small-scale farming took place at the Manse. These included three corn stacks, one stack of ryegrass, one stack of meadow hay, a quantity of excellent potatoes, a field of turnips, three milk cows in calf, a two-year old quey (a young cow), a stirk (a heifer or a bullock), two pigs, a horse and cart, a plough, a pair of harrows, a stone roller, a pair of fanners (equipment for separating grain from chaff) and a thrashing board. The following month, all of Rev. Graham's books and those of his late father, Rev. Dr Patrick Graham - about 400 volumes in total - were put up for sale by public auction. See also:

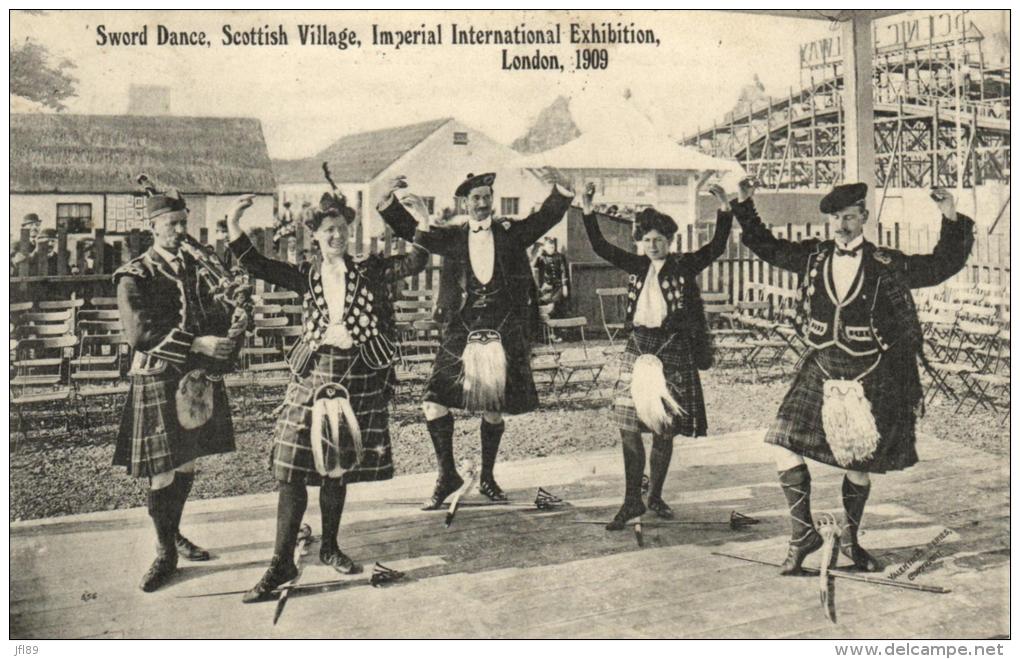

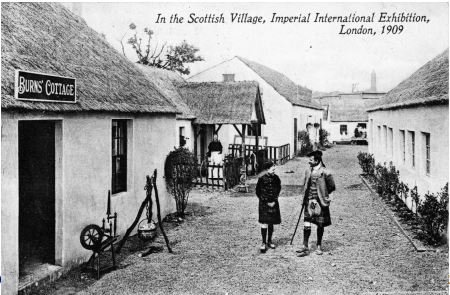

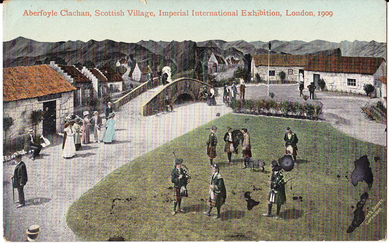

Blog post by Louis Stott which includes information about Rev. Dr Patrick Graham http://louisstott.com/tag/r-b-cunninghame-graham  Kindly lent by J. Clow Kindly lent by J. Clow In 1909 Aberfoyle was recreated as a quaint, picturesque model village at the Imperial International Exhibition held in London that year - complete with Highland sword dancers and Shetland ponies. Alongside 'native villages' and human zoos, international exhibitions and World's Fairs of the 19th and early 20th century often featured Scottish, Irish and other 'national' villages. They were created as highly idealised pastiches of Highland life, intended to promote idyllic rural life and traditional skills, customs and values, and they were popular with exhibition visitors. The International Imperial Exhibition held at Shepherd's Bush in London in 1909 had a Scottish village, part of which represented the Clachan of Aberfoyle. The village also included replicas of Burns' cottage and John Knox's house, it had a post office and a team clad in Highland dress. Each day they would perform sword dancing and re-enact scenes from Sir Walter Scott's novel 'Rob Roy'. While the neighbouring Irish village was given the made up name of 'Ballymaclinton', the Scottish village was named after the Clachan of Aberfoyle. The real clachan of Aberfoyle, through Scott's writing, was embedded in public imagination and an obvious analogy for the Exhibition's romanticised hotch-potch village. See also: Local historian and author Louis Stott has written a piece about the Scottish village for the Strathard News; read it here http://www.strathardnews.com/issue%2054.pdf  Kindly lent by J. Clow Kindly lent by J. Clow The placename Fielbarachan, preserved until recently in 'Fielbarachan Guest House' in Aberfoyle (now Craigmore B&B), possibly reflects an association with the medieval saint St Berchán. Fielbarachan, or in Gaelic Féill Bhearcháin, means 'the fair of St Berchán' and is thought to relate to an annual fair which took place in mid October in Aberfoyle. The name Fielbarachan applies to a field opposite the guest house, which was used for the local games as late as the 1930's, and it is possible that this too was the site of Aberfoyle's ancient fair - the fair of St Berchán. This information is derived from research by Dr Peter McNiven into the Gaelic place-names of medieval Menteith and from the 'Commemorations of Saints in Scottish Place-Names' website, details below. http://saintsplaces.gla.ac.uk/place.php?id=1394961385 http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2685 https://archive.org/stream/bethadanemnrenn00plumgoog#page/n334/mode/1up Harry Bedford Lemere was one of the best known architectural photographers of the late 19th and early 20th century. Around 1890/1895 he photographed the newly erected houses in Craiguchty Terrace. The photographs you see below are held in the collection of the RCAHMS (click on the photographs for more details, and to access two additional interior shots). A blog post by the Royal Institute of British Architects confirms that many architects commissioned Bedford Lemere & Co to photograph new premises or works, and I imagine this was the case for Craiguchty Terrace too. Designed by Glasgow-based architect James Miller the six terraced houses had recently been completed, and I am wondering if Miller commissioned Bedford Lemere to document his latest work.

About 20 years ago or so I heard a researcher give a paper on the display and interpretation of medieval Icelandic manuscripts in a particular institution in Iceland; the name of the speaker and which specific institution it was I can no longer remember, I am afraid. In the paper he made a brilliant analogy which has stuck in my mind ever since. He described how these priceless treasures of Icelandic cultural and literary heritage were displayed in glass cases with tiny labels giving the manuscript number (for example 'AM 145 fol. 1v'), a date and little else. The manuscript might have been a page from an Icelandic saga and, as such, the physical link between the viewer and the world within the saga - a magical remote world full of violence, heroic deeds, intrigue, conflict, bloodshed and suspense, all the key ingredients of first class entertainment. To anyone interested in engaging with such an incredible piece of material culture and history being offered nothing but the manuscript number and a date would be like going to the cinema to watch a James Bond film, and instead of getting to watch the film, all you got was a picture of Sean Connery and a label saying: JB Goldfinger, 105 mins, 1964. That would be really rather disappointing...The point the speaker was making was that without interpretation or visualisation to make an object, in this case a folio page, come alive, all the things that make it fascinating and valuable remain locked inside. The utterly gripping tales of Iceland's medieval past would remain inacessible to everyone bar a handful of specialist scholars.

|

homeauthorKat Dalglish archives

March 2017

categories

All

Me at Blipfoto

|